Refugee Resettlement, Devastated by Trump, Finds a Long Road to Recovery

By Sara Staedicke | April 18, 2021

A family awaits resettlement in the U.S. at the Refugee Support Center for Turkey and the Middle East in Istanbul (Photo: ICMC/ Guido Dingemans)

Refugee resettlement in the United States was brought to a standstill under the Trump administration as each year brought a new record low cap on the number of refugees admitted, and policy changes wreaked havoc on the system that protects and resettles some of the world’s most vulnerable.

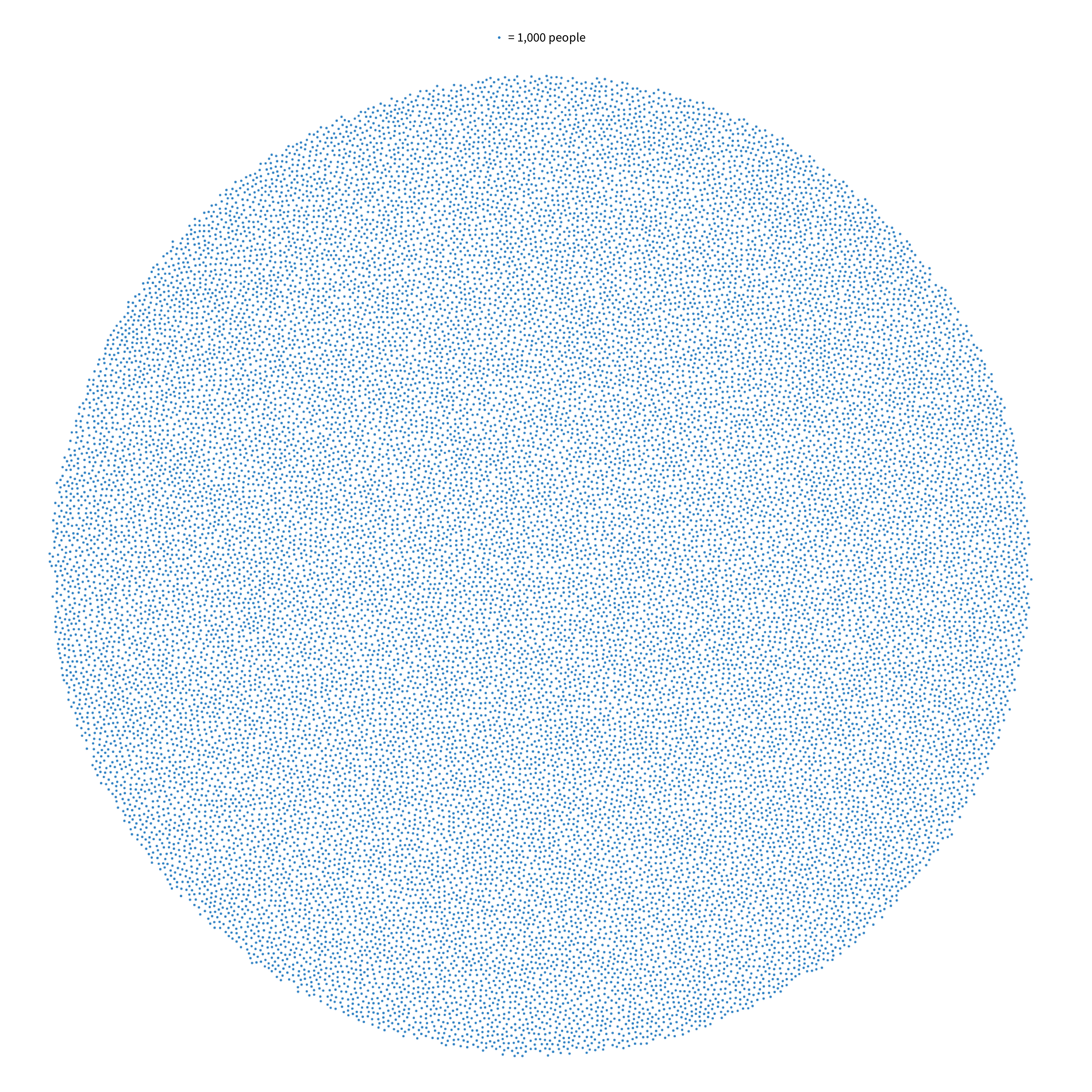

Nearly 80 million people have been forced to flee their homes globally as of 2019. 26 million are refugees, who are unable or unwilling to return to their country of origin because of a well-founded fear of being persecuted for reasons of race, religion, nationality, membership of a particular social group, or political opinion. According to UNHCR, 1.44 million refugees are in urgent need of resettlement, yet less than .25% of all refugees are resettled. The United States has historically resettled the most refugees worldwide, yet fell behind Canada as the leading resettlement country in 2018 amid cuts under the Trump Administration. The decline in the U.S. has been followed by low quotas in other countries, leading to a record low number of refugees resettled worldwide in 2020, even as global displacement is at an all-time high.

In 2019, there were 26 million refugees globally

107,729 of them were resettled in a safe third country

27,514 were resettled in the U.S.

Joseph

Joseph was the plaintiff in the Doe et al v. Trump court case challenging the first travel ban. When he was ten, he and his family fled fighting in Somalia’s civil war, a journey that his sister did not survive. The rest of the family made it to Kenya, where he spent nearly 22 years living in refugee camps. Joseph eventually met his future wife in the camp, and they had three children.

In 2014, his case to be resettled in the U.S. was finally approved, but he could not bring his wife or children because his case had been filed when he was a minor. After arriving in Seattle, he applied for his family to join him—a process that took years of medical and security screenings.

At the end of their rigorous vetting process, their reunion was upended by the travel ban because Somalia was considered one of the “high risk” countries, despite the fact that his three sons were born in Kenya and had never set foot in their home country. After five years of separation, the family was finally reunited in 2018. While they were at last unified and the first travel ban rescinded, the Trump administration issued subsequent discriminatory bans and policies to bar Muslim and African refugees to the U.S., putting countless families in similar situations.

I had bought them beds, dishes, plates back in 2017 when I thought they’d be arriving. Every time I look at the stuff I bought them, I think, ‘Will we ever be able to see them?’

—Yasmin Aguilar

Refugee and Immigration Specialist, Agency for New Americans

Yasmin

Yasmin fled war in Afghanistan in the 90s and moved to Pakistan but found herself in danger there too. She was a doctor and made trips back to Afghanistan to educate women about sexual health and abuse. It was risky work and she was kidnapped by a militant group in 1992.

Yasmin was eventually able to come to the U.S. as a refugee in 2000, but she was the only one in her family able to come. And in exchange for her safety, she had to give up her career in medicine, because her credentials weren’t recognized in the U.S. In spite of this, she has spent the last 2O years supporting refugees and survivors of torture in Boise, Idaho.

One of her sisters was resettled in Australia after the Taliban killed her husband. But her other brother, sister, and niece remain in Pakistan, where she’s only been able to see them twice in the last two decades. They applied to be resettled in the U.S. in 2015 and were approved in 2017, but like many, their case has been delayed due to cuts on refugee admissions. They’ve gone through medical and security screening every six months for the past three and a half years, but their case is still processing.

When Biden was elected president, her 11-year-old niece said, “Joe Biden will hopefully put me on the first plane. He’s a friend of Obama, and Obama loves Muslims.”

Yet, they’re still waiting today.

The last four years saw the lowest caps on refugee admissions in history

Since its establishment in 1980, the formal U.S. Refugee Admissions Program has admitted 3 million refugees, largely guided by a presidential determination each year that sets an annual cap on admissions. Historically, refugee resettlement has been a bipartisan issue and the average ceiling from 1980-2016 was around 95,000 under both Democratic and Republican administrations. Before leaving office, President Obama raised the refugee ceiling to 110,000 in recognition of record global displacement, notably from conflicts in Syria, Iraq, and other countries. However, upon taking office, Trump quickly cut the cap for FY 2017 by half and each year has seen a new record low, ending in a cap of 15,000 refugees for FY2021.

Source: Worldwide Refugee Admissions Processing System (WRAPS) data from the State Department’s Bureau of Population, Refugees, and Migration.

Note: Refugee Admissions for FY2021 are through March 31, 2021.

In February 2021, President Biden pledged to raise the cap on refugee admissions to 125,000 in FY2022, and 62,500 for FY2021, which represents an ambitious four-fold increase with just months remaining in the fiscal year. However, after signaling this change, his administration has stalled in completing the official determination, leaving Trump’s ceiling in place.

Amid a flurry of policy changes, refugee admissions dropped by 86%

Under the lowest refugee caps in history, actual refugee admissions to the U.S. declined by nearly 90%. The successive travel ban iterations suspended entry for citizens of certain “high risk” countries, tried to suspend the admission of Syrian refugees indefinitely, and halted all refugee admissions for 120 days. The administration also added additional vetting requirements that dramatically slowed processing times and ended refugee referrals from UNHCR, which is the largest source of refugee referrals worldwide. It also required states and localities to affirmatively opt-in to refugee resettlement in their jurisdictions, though 42 did opt in and only Texas declined. While historically the refugee ceiling has been allocated by region based on humanitarian need, the Trump administration replaced the regional allocations with an extremely rigid category-based system which effectively made many of the 120,000 refugees already in various stages of the resettlement pipeline no longer eligible.

Policy changes have shifted the demographic origins of refugees admitted

These discriminatory bans and policy changes had significant effect on those admitted to the U.S. Refugees from the Middle East made up 37% of all admissions in 2016, but just 13% in 2020, while the European share increased from about 5% to 16%. In comparison to global figures, 68% of all refugees come from Syria, Venezuela, Afghanistan, South Sudan, and Burma. The three successive travel bans essentially brought refugee admissions from a select group of countries deemed “high risk” near zero. For instance, admissions from Syria and Somalia plummeted by 96% and 98% over the four-year period.

In addition to country of origin, there has also been dramatic shift in the religious affiliation of refugees admitted over the last four years. In 2016 about 45% of refugees admitted to the U.S. were Christian and 45% Muslim, with the remainder split between smaller religious groups. In 2020, 74% of admissions were Christian and 22% were Muslim.

Display by

With cuts to refugee admissions and funding, resettlement organizations have shut their doors

As a result of the dramatic decline in refugees resettled in the U.S., resettlement organizations, which receive funding to support refugees based on the number of refugees they resettle, saw their budgets plummet as well. These organizations place refugees in communities once approved for placement in the U.S., help them find housing and employment, assist with enrolling children in school, and many other essential areas of assistance. The funding cuts resulted in the closure of about a third of all resettlement offices in the country. Many have had to shutter their offices completely, or downsize and merge with other offices, and layoff large portions of their staff.

Right off the bat you have half of the budget projected, but even that is not certain, because it’s only going to materialize if and when the families arrive.

—Etleva Bejko

Director of Refugee Resettlement for Jewish Family Service of San Diego

Much of the international infrastructure supporting U.S. refugee resettlement has taken a hit as well. In 2019, USCIS announced the closure of 16 international offices, leaving just 7 in operation, which support U.S. officials who travel abroad for refugee interviews and screenings, among other responsibilities. There have also been reports that many Refugee Corps officers have been diverted to work on asylum cases instead. Between 2016 and 2018 there were on average 500-550 asylum officers and 120-190 refugee officers, with at least 80 refugee officers diverted to the Asylum Division in 2018. Historically, the U.S. has provided humanitarian relief to both refugees and asylum seekers, but in the last few years of the Trump administration, the asylum case backlog became a talking point for downsizing refugee resettlement.

Gearing up to meet the ceilings for 2021 and 2022

It's not a light switch that you turn off, and then two years later you turn it back on.

—Matthew Soerens

U.S. Director for Church Mobilization, World Relief

President Biden has promised ambitious new ceilings that would restore the humanitarian values of the U.S. Refugee Admissions Program, but the road to recovery will be long and key steps have been lagging. Despite submitting a report to Congress on a proposed emergency presidential determination on refugee admissions that would raise the current ceiling from 15,000 to 62,500 and restore the regional categories, the Biden administration has delayed signing the official presidential determination for two months, leaving Trump’s policies in place. After the Report to Congress was submitted, the State Department began scheduling flights for already-approved refugees in anticipation the determination would be signed quickly as it has in the past, but with no signature, it had to cancel the flights of more than 700 refugees, many of whom have been waiting in limbo and dangerous situations for years. Many had sold all their belongings in preparation for their arrival in the U.S., only to be told their travel had been cancelled and their arrival date unclear. Among those who had their flights cancelled was a pregnant Congolese woman who can no longer travel because she is in her third trimester. And once she delivers her baby, the child will have to go through a separate screening process, which could take months.

After significant delay, the Biden administration announced mid-April that it would keep the Trump-era refugee cap at 15,000 for FY2021, walking back from its earlier promise to raise the cap to 62,500. Only when met with outcry from Democratic lawmakers and refugee resettlement organizations, did the administration announce it would release a revised, increased refugee cap in May.

Given the decimated refugee admissions program we inherited, and burdens on the Office of Refugee Resettlement, his initial goal of 62,500 seems unlikely.

—Jen Psaki

White House Press Secretary

Yet when the new ceiling is finally signed, it will still be an uphill battle to restart the U.S. Refugee Admissions Program as much of resettlement organizations’ capacity has been decimated. Many organizations have reported that their relationships to the local community, upon which they depend to provide services to newly resettled refugees, have been weakened as a result of the closures. The Biden administration has also proposed piloting a private sponsorship initiative. This type of program, which has had success in Canada, would allow private individuals to fund or provide resettlement services for refugees. This would make resettlement organizations and faith-based organizations, who have seen their resources dwindle, even more essential to successful refugee integration.

Some organizations have argued for enacting the Guaranteed Refugee Admission Enhancement (GRACE) Act, which would create a minimum refugee ceiling in line with historical trends that would make the resettlement program less vulnerable to an individual president’s whims. Others point out that the goal should not be to get back to what they had under Obama, but to build a better resettlement program that is less ridden with delays and could be more flexible to individual refugees’ needs rather than the current model, in which all refugees must become fully self-sufficient after 90 days of initial support.

Refugees take part in a cultural orientation session aiming to prepare them for life in the United States (Photo: ICMC/Guido Dingemans)